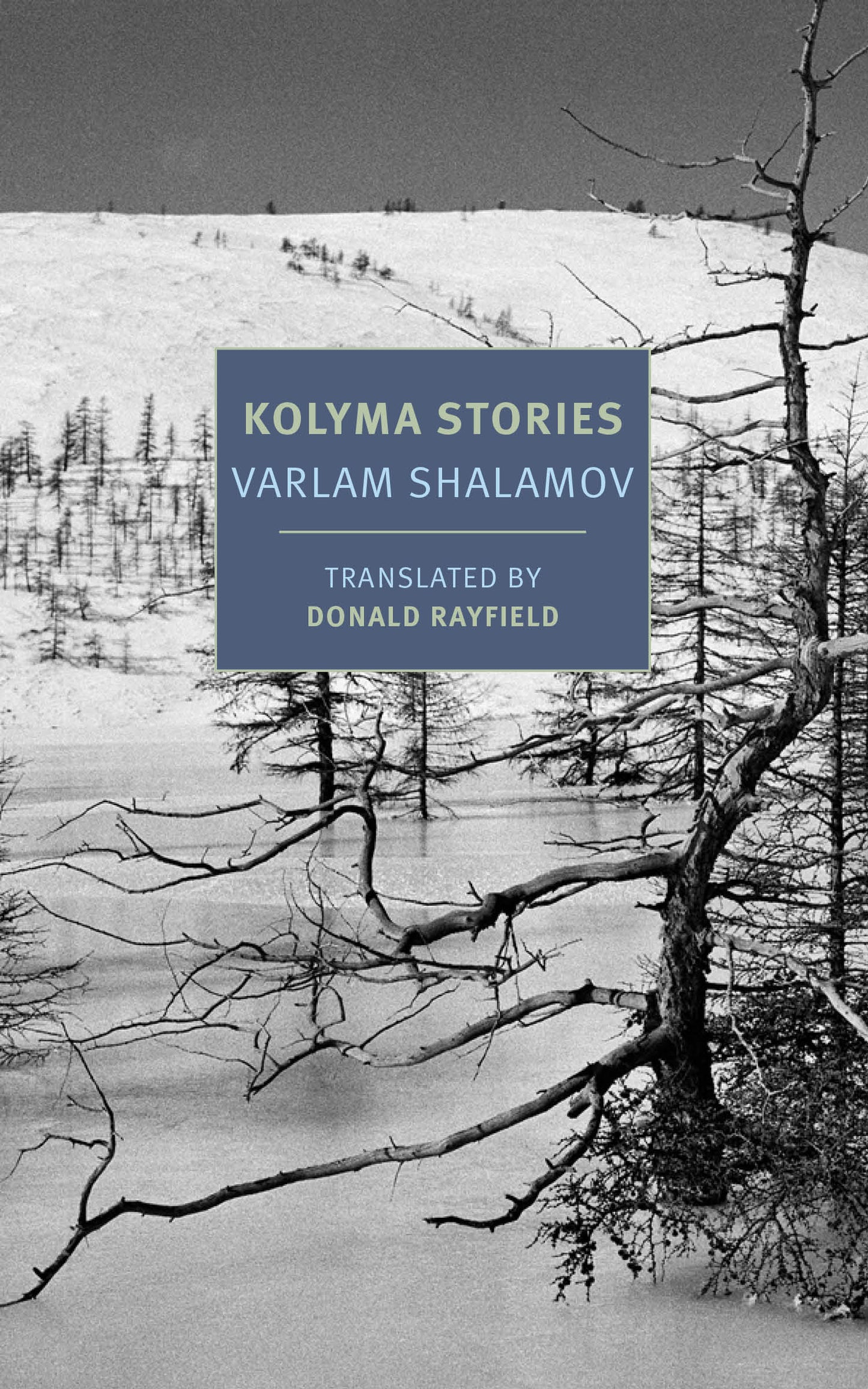

Nominated for the 2020 Read Russia Prize

'Every story of mine is a slap in the face of Stalinism,' Shalamov wrote in 1971. . . . Shalamov’s stories are slaps in all our faces—and, like a slap, they can enliven as well as hurt. . . . Shalamov is not only a unique witness, but also a fine poet and one of the greatest of Russian writers of short stories. He is as important a figure as Primo Levi.

—Robert Chandler, Financial Times

As a record of the Gulag and human nature laid bare, Varlam Shalamov is the equal of Solzhenitsyn and Nadezhda Mandelstam, while the artistry of his stories recalls Chekhov. This is literature of the first rank, to be read as much for pleasure as a caution against the perils of totalitarianism.

—David Bezmozgis

Available only for the last five years in Russia itself, a searing document, worthy of shelving alongside Solzhenitsyn.

—Kirkus Reviews, starred review

The book is packed with gems, each complete in itself. Together they form part of a mosaic unlike anything in world literature. A struggle with memory comparable with that of Proust or Beckett, this is a work of art of the highest order by a writer of extraordinary daring and ambition . . . He resembled Chekhov in his combination of non-judgemental realism with unyielding severity in his view of the human world.

—John Gray, New Statesman

There is pleasure and perturbation in this huge collection. Shalamov’s writing has a light, clear-eyed quality, even if the subject is the inhumane futility of life in the Soviet gulag.

—The Irish Times

These new translations of Varlam Shalamov’s astonishing short stories may well establish Shalamov as the new laureate of the Gulag . . . The power of fiction has never been better exemplified . . . Shalamov’s unique tone of voice and his pared-down style are beautifully rendered here by Rayfield — limpid, assured, the scarce moments of lyricism expertly caught . . . One feels that poor Varlam Shalamov would be both amazed and delighted.

—William Boyd, The Sunday Times (UK)

Varlam Shalamov’s short stories of life in the Soviet Gulag leave an impression of ice-sharp precision, vividness and lucidity, as though the world is being viewed through a high-resolution lens.

—Charlotte Hobson, The Spectator

Suffering—elemental suffering—can never be told. There is no other state where the distance between a narration merely truthful and a narration that is truth itself creates such an achingly unfathomable abyss. It is this that elevates the work of Varlam Shalamov. His torturous secret resides in how the focus of his attention is turned only toward the frozen crenellation of palpable concrete details. What he knew about the human being was appalling. And although none of this can be transmitted—nonetheless, he transmits it to us.

—László Krasznahorkai

Shalamov's experience in the camps was longer and more bitter than my own . . . I respectfully confess that to him and not me it was given to touch those depths of bestiality and despair toward which life inthe camps dragged us all.

—Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

[Shalamov's] prose is as simple and spare as a scientist's. The stories are exciting because they deal with extremes, like stories of Shackleton's expeditions, or Jack London's Klondike tales . . . Sit with them long enough and you begin to sense the depths of feeling under the permafrost, and something approaching Chekhovian artistry . . . these stories are literature—great literature, with their own terrible beauty.

—Alex Abramovich, Bookforum

Like the landscape gardeners of the late 18th century, Shalamov builds ruins. The sketches remain fragments because they are about fragments—of men, of society, of dreams.

—Jay Martin, The New York Times Book Review

There can be no doubt that Shalamov’s reportage from the lower depths of the Gulag of a society building a ‘new world’ will remain forever among the masterpieces of documentary or memoir literature and an invaluable source for the present and future understanding of the ‘Soviet human condition.’

—Laszlo Dienes, World Literature Today

A numbness of sorts pervades the tales as a whole, as if the accumulation of horrors could not be related or understood except under very heavy sedation. In Andrei Sinyavsky’s apt characterization of Varlam Shalamov: ‘He writes as if he were dead.’

—Maurice Friedberg, Commentary